1.12.16 ‘Keep me in your heart for awhile’

Ten years before he died, I spoke with Warren Zevon.

It was 1993, and he had no reason to believe he didn’t have a long, long time left as a musician and a human being.

“We’re past the end of rock and roll,” he told me. “In our time, nothing lasts really long. But to nostalgically believe there is a rock ‘n roll music is unwise, because then our eyes will be closed when the Virtual Reality Picasso comes along. I think rock ‘n roll is Neil Young. I think rock ‘n roll is the Rolling Stones. And I think it’s perfectly appropriate when they’re 60 to sing about being horribly misunderstood old people as it was to sing ‘My Generation.'”

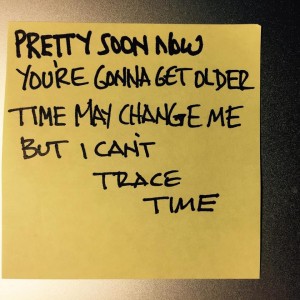

It is 2016 and David Bowie is dead. He went out, loyal to himself to the bitter end: Without telling anyone he was going, but leaving behind a record (Blackstar) that came out just days before he breathed his last. It echoes with final thoughts and dreams of mortality; a video from it kills off Major Tom for the last time while elevating the mythic astronaut to godlike status (were those jewels always beneath the skin?). Bowie knew what was coming, kept it to himself (and his family), and soldiered on making art. It is an extraordinary last gift to leave us with, and the more I learn the more awestruck and gutted I am about the entire matter.

But Zevon did it first.

“It’s always really hard work, it’s really frustrating hard work,” he said to me in 1993. He would be diagnosed with inoperable peritoneal mesothelioma (cancer of the lung’s lining) in 2002, and would die the following year. “‘Writers block’ is just a description of it being harder. So if it’s hard to write a sentence, you just write a word, and if you can’t write a word you can’t beat yourself up over it. If you’re in the season of needing to write you have to be able to write everywhere. Like most writers, the season comes with the deadline. It may be an internal deadline, like ‘What the hell am I doing on this planet if I haven’t written a song in a year in a half?’ — [but] nah, it takes a business deadline. And then I just start listening to everything and considering everything, listening to the resonance of every phrase.”

I was — am — a bigger David Bowie fan than I ever was of Zevon, but I had — have — incredible respect for Warren. His songs are funny, fantastical, dark, evil, bewitching. And in the wake of his cancer diagnosis, Zevon did something I never imagined an artist would do: Go public with his impending demise, and even more public with his impending new album. I know exactly where I was when I watched the documentary he made for VH1 about the making of The Wind, and I know that by the next day I wanted to grip him by the lapels and ask him so many questions: How could he go on? How could he continue to create? What was it like to preside over your own pre-funeral? Why would you ever start a new relationship with someone just as you were preparing to finish your time on earth? Was it cruel or incredibly human?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hIaOHkeQNMk

That last element — the fact that Zevon was in a new relationship with a young woman, who was featured in the documentary — stuck with me, and eventually I put a word down, then a sentence, and then more … but that’s for another time.

“It’s certainly easier to write about conflict than it is to write about — if we lived in a perfectly harmonious world there’d be less to write about,” he told me. “But I think of songwriting in some ways like acting. I think most actors are interested in playing villains; I think they may regard it as modest that they don’t want to be the hero, they don’t want to be the sheriff. It’s probably just an inclination I have to play certain kind of parts. I have a certain kind of voice, I can only sing triplets when the moon is full, I’m not a tenor so my voice doesn’t lend itself mechanically to playing pretty songs.”

But he did come up with some very pretty, and very hard-edged, tunes for The Wind. The two that stick with me are “Disorder in the House,” which cranks up the guitars and features Bruce Springsteen, and ends with the lines: “Disorder in the house/ I’ll live with the losses/ And watch the sundown through the portiere.” It’s a bumpy, growling sort of tune — very Zevon — but also impossible to listen to without that tinge of thinking that his sundowns were getting limited.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACSeVC6umzg

Then there’s “Keep Me In Your Heart,” the last song on the record, the last one he recorded — and it has a magical quality of wish fulfillment, because after hearing it he is indeed in your heart, living and lingering there, still playing the guitar:

Shadows are falling and I’m running out of breath

Keep me in your heart for awhileIf I leave you it doesn’t mean I love you any less

Keep me in your heart for awhileWhen you get up in the morning and you see that crazy sun

Keep me in your heart for awhileThere’s a train leaving nightly called when all is said and done

Keep me in your heart for awhileSha-la-la-la-la-la-la-li-li-lo

Keep me in your heart for awhileSha-la-la-la-la-la-la-li-li-lo

Keep me in your heart for awhileSometimes when you’re doing simple things

around the house

Maybe you’ll think of me and smileYou know I’m tied to you like the buttons on

your blouse

Keep me in your heart for awhileHold me in your thoughts, take me to your dreams

Touch me as I fall into view

When the winter comes keep the fires lit

And I will be right next to youEngine driver’s headed north to Pleasant Stream

Keep me in your heart for awhileThese wheels keep turning but they’re running out

of steam

Keep me in your heart for awhile

It is the song of a man who is getting on the train, and heading to a place where we cannot hear him sing new things, a place that none of us know the first thing about — but a destination we will all reach eventually. It is impossible for me to hear this song without wanting to burst into tears. It is brave, it is sad, it is powerful, it is strong in its most broken places.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1KjRLq4uF4A

We put a lot on to our heroes, our entertainers, the people who make us feel all the feels. We want to thank them and don’t have the language to do so, so we buy and watch and record and ask for autographs if we happen to cross paths but it is a vocabulary of gibberish. They are creating from a well from which we can only bathe, not drink and so we can never fully know what is going on as they weave mystic dreams out of sound and vision.

David Bowie was one of our greatest artists in so many ways. Warren Zevon may have been a lesser light, but only by degrees — and still, of a magnitude greater than most any of us can ever hope to achieve. In their final hours they remained both selfish and unselfish at the same time: they persisted in their creation so it could be shared for the world — and in doing so set in stone the context for what we would hear. It will be impossible to listen to Blackstar or The Wind and and not know they are the last of their kind. And so we are left with a bittersweet memory: This is the last they had to offer, and their creators knew it at the time.

“‘Start Me Up’ is one of my favorite songs, and I definitely didn’t write it,” Zevon told me. “I’ve always said I write songs because I want to hear them. I try to write my own hit parade. There’s no other reason to write songs. My job is to write the songs I want to hear, and record them in a way that whatever I’ve heard seems the most entertaining recording, and work on it until I’m so sick of it I can’t listen to it myself.”

In the words of Jimmy Fallon, who paid tribute to Bowie on The Tonight Show Monday, “Play it loudly. And just thank him. Thank you, thank you, thank you.”

They’re all the words we have, after all.

xo,

R